Thoughts on Parashat Pinchas

At the very beginning of this week’s Torah portion God rewards Pinchas, the grandson of Aaron, for his zealous act – namely for killing the prince of the Simeonites Zimri and his lover Cozbi, a Midianite princess. As part of this reward God endows Pinchas with the covenant of peace and includes him in the priestly line for eternity (According to Rashi he was not part of it before; Pinchas did not take part in the priestly anointment of Aaron and his sons [Shemot/Exodus 28:40-41.])

Pinchas’ killing of Zimri and his lover is often portrayed as an impulsive act of “mob law”, which makes this text quite problematic for our tradition. In the eyes of a modern person that act looks like a brutal, ruthless murder, carried out by a (religious) fanatic, and that is exactly how a similar act would be treated in most judicial systems in the modern world. In fact, this is not only a contemporary way of looking at it – this story was already viewed as challenging by the rabbis. Zimri’s and Cozbi’s violent, willful execution without due process of law contradicts the fundamental rabbinic principals of justice, especially when it involves such a serious issue as the death penalty.

But is this actually the correct way of looking at this story? It’s worth to take a look at what happened – according to the Biblical text – before Pinchas carried out his act.

As it turns out, the people of Israel, as they were staying in Shittim, start to engage in harlotry with Midianite women (Numbers/Bamidbar 25:1.) In the Hebrew text we have the verb liznot, which in more euphemistic translations is rendered as “commit harlotry” (the best euphemism can be found in Cylkow’s translation: “they courted them”.) In the English translation of the Jewish Publication Society the word “whoring” is used (which in Polish could be translated, equally euphemistically, with a word meaning “to engage in prostitution”.) The text also says that it was the “nation” who was engaging in these excesses, so we can assume without any trace of doubt that it was a mass scale activity.

Shortly after that God orders Moses to carry out a public execution (probably by impalement) of all the current Israelite leaders) (Hebr. et kol roshei ha’am, Numbers/Bamidbar 25:4), which shows the scale of corruption in the Israelite society. The next verse suggests that Moses is trying to change and soften God’s decree by limiting it only to those Israelites who directly engaged in harlotry and who served a foreign deity. Shortly after that Zimri, along with his lover, appear ostentatiously before the Tent of Meeting, in front of which Moses with a group of Israelites are weeping in despair. Then they go to a nearby tent to do you-know- what. This is when Pinchas appears and kills them both in the tent.

As we can see, we are dealing with quite an extreme situation. For this reason, as well as for several other ones (which I discuss below) I believe that viewing Pinchas’ action as an impulsive act of “mob law” is not entirely correct and it’s a serious simplification. For his action takes place in a certain legal context – the death sentence issued by the Eternal Himself for those responsible for this whole situation – and there are also certain circumstances justifying the action itself – namely the relatively lenient stance of Moses towards this whole situation. This is why Pinchas is being rewarded by God for his religious zealotry, since a lot in this story points to the fact that he was indeed the first one to appropriately carry out the Divine decree.

And while to us, modern people, this might seem barbaric, Pinchas through his actions in fact atoned for Israel’s sins. Not only did he take upon himself the blame for doing something which in principle is prohibited, but he also took responsibility for changing the course of events, which, if no one had stopped it, sooner or later would have led to a catastrophe for the entire society. Of course we don’t know for sure how this story would have turned out if it hadn’t been for this murder, but the answer which the Torah itself gives us is exactly this – that by carrying out this act of “mob law” on Zimri Pinchas put an end to God’s wrath, which otherwise was going to spill over the entire society of the chosen people. (Numbers/Bamidbar 25:11-13.)

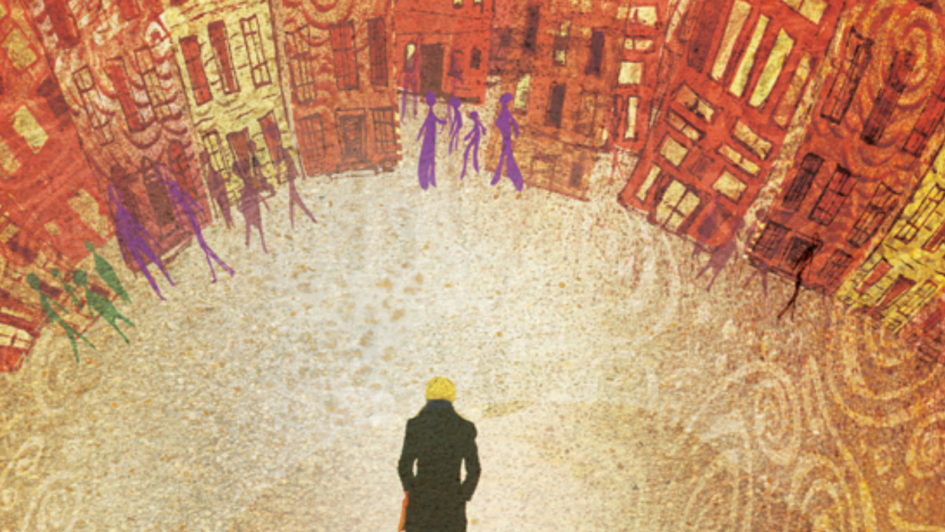

The story we read in our Parasha is yet another (albeit quite radical in its content) story about how fixing the state of our societies – whether on a micro- or macro-scale – is usually not a nice, pleasant and likable task. This story also provokes many questions – for example, what can an individual who has maintained their morality and a clear mind do in a situation when they see with absolute certainty that the entire society they live in has succumbed to madness? Should they go out and try to convince, teach and change people’s minds? Should they withstand derision and humiliation? Would Pinchas (or anyone else) be able to arrange an “honest trial” for the people who were plunging the society into decay, given that God has already sentenced to death the elite of this very society for the same (as we can assume) sins? Would any kind of honest trial be possible in the circumstances which are being described in our story? To portray this issue in contemporary terms, we could ask: Is there a chance for an honest trial in a society whose leaders, including the judiciary branch, are utterly corrupt and for example collaborate with the mafia?

Unfortunately, the methods used to repair a society must match the level of madness that society has succumbed to. And human societies cyclically plunge into different kinds of madness. We know this perfectly well from our human history and there is not much to suggest that this situation will ever radically change.

Fighting evil and moral and social decay is certainly possible with the use of less radical measures, but this depends on the balance between good and evil forces. If a significant majority of force is on the side of good, then – let’s call them “gentle” – methods can be effective. If the force is on our side, we can influence people who are doing evil things by means of admonishments, lenient punishments and so on, since they are surrounded by the forces of good and adapting to the principles of justice is in their best interest if they don’t want their lives to turn into hell. In such cases repaying evil with good also has a chance to work. The situation gets more complicated when the balance of forces shifts and becomes more equal, like for example in family or marital conflicts, when one side has definitively found themselves on the dark side of force (in case of alcoholism, crimes, pathological infidelity and so on.) In such situations gentle methods lose their power and more radical solutions, such as divorce or separation, need to be implemented. If the significant majority of force is on the side of evil, then no gentle, peaceful methods will ever work; the individuals who try to use them usually become martyrs. That’s why, before we judge the way someone acts in extreme situations, let’s first take a close look at the balance of the external and internal forces of good and evil in which that given individual is entangled as they carry out their actions.

Shabbat Shalom!