A clash with the Divine reality of eternal transformation.

Since human interests have an inherent tendency to come into conflict, no society can exist without laws and law-enforcement institutions. Thanks to laws which regulate interpersonal relations and their efficient enforcement an organized and peaceful societal life is possible, which in turn contributes to the development of that society – if the law is well-considered, wise and effective.

However, there are boundary situations in our lives when all the laws – or, to be more precise: almost all or their vast majority – are suspended. According to our tradition that suspension of laws occurs in life and death situations. To save human life (pikuach nefesh – literally watching over a soul) all existing moral laws can be suspended with the exception of three prohibitions: against murdering, immoral sexual relations (gilui arajot) and idolatry. And if someone’s close one dies, the mourner is not only exempted from a number of religious and secular duties, but some of them are explicitly forbidden (such as paid work – for at least 3 days, depending on the person’s financial status, or for example the study of Torah, which by definition is a joyful act).

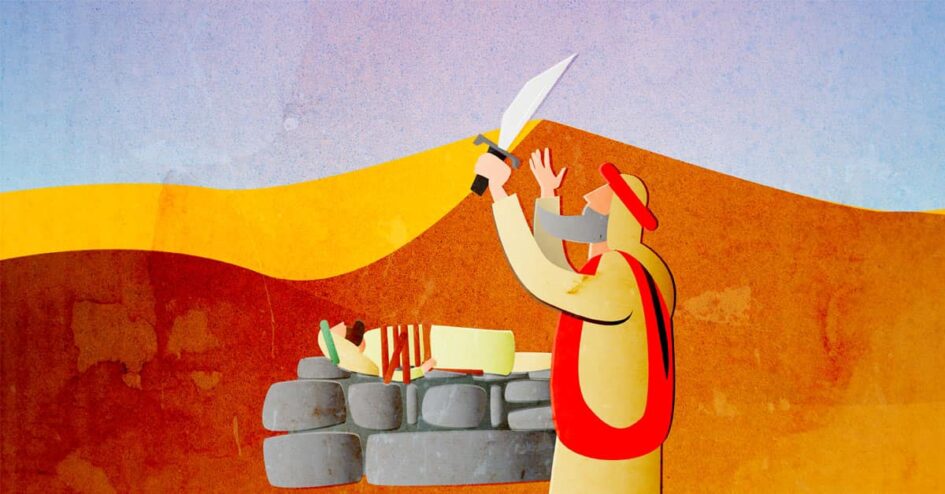

So it seems that in Judaism the suspension of certain or almost all laws applies to situations which are – according to tradition – decided by God. God is the One who gives life and the One who takes it away; the One who interferes to save it and the One who seems to keep silent in the face of doomsday events on Earth. We have a similar situation, which leads to the suspension of certain moral laws, in the case of Akedah, i.e. the story of the Binding of Itzchak, which we read in our Torah portion for this week:

Some time afterward, God put Abraham to the test. He said to him, “Abraham,” and he answered, “Here I am.” And He said, “Take your son, your favored one, Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the heights that I will point out to you. (Gen 22:1-2)

As we know, there is an enormous amount of interpretations of this story, both within and outside the Jewish tradition. But we won’t be mentioning them here. I propose, quite reasonably, that we view Abraham’s and Itzchak’s situation as an example of those boundary situations, life and death situations, in which everything is decided by God. God is an endless potential for the world’s transformation. Since in one instance He can decide about the shape of the whole world, He can also decide to suspend its laws, which are secondary to the real world – they either describe it or they normalize it.

Considering that the most fundamental moral law – You shall not murder – is being suspended in the story of the Binding of Itzchak, we can rightly believe that all moral laws are being suspended here. In such a case the only law is the will of God Himself. God decides to put Abraham in this reality and this is what this test is about.

In our story God is disagreeing with Himself – at first he makes one decision (to sacrifice Itzchak), only to “change His mind” shortly after and save Itzchak from death. God puts Abraham in this situation on purpose to test his reaction. As we already know from the same parasha, Abraham is capable of arguing with God (the negotiations regarding the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Gen 18:20-33). In this new situation God is checking if Abraham is also capable of being completely obedient to Him. Abraham passes this test (although unfortunately at the cost of his son’s psychological trauma) and God views him as a righteous one, and therefore worthy of being “the father of nations”.

Abraham’s trial is a test if he can fully embody God’s will, even if it’s incomprehensible. So not only are all the laws and ethics suspended here, but human reason as well. Abraham was capable of doing all this for the sake of carrying out God’s will, but that’s not all. In a sense this was only the beginning. An experience of a close one’s death, the nearness of a close one’s death or the nearness of one’s own death permanently changes our character. These are events which orient us in our lives. They ultimately teach us what is truly important, what is truly essential in life, and what is only an illusion, devoid of any meaning. They polarize us morally. That’s the baggage that both, Abraham and Izchak, came out with from this experience. Laws, both natural and moral ones, are secondary to Divine reality and are dependent on it. God is an endless potential for the world’s transformation. Abraham clashed with that endless, Divine reality of transformation and survived that clash by fully devoting himself to it. Until the very end he didn’t know if he’d ultimately become the father of the nations or not. At the end Itzchak was given to him once again, so the Divine promise has been fulfilled twice and the world has followed the path planned by God.

Shabbat Shalom,

Menachem Mirski

Translated from Polish by: Marzena Szymańska-Błotnicka

This d’var Torah was commissioned by Beit Polska

– Union of Progressive Jewish Communities in Poland.