Thoughts on Parashat Miketz.

How should we live? On what basis should we make life choices? Should we trust God, ourselves, or maybe other people, for example those from the government? Or maybe we should trust only some people, or for example experts and science and technology?

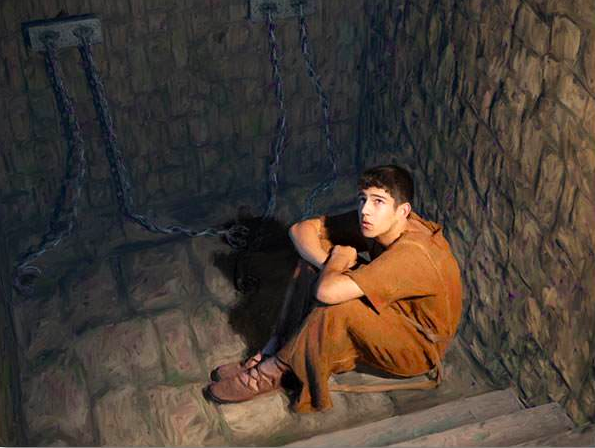

Of course we can find answers to these questions in the Torah and Rabbinic literature. Last week’s Torah portion ends with the story about Joseph interpreting the dreams of the cupbearer and the chief baker. According to the prophecies conveyed in both dreams the chief baker will be sentenced to death, whereas the cupbearer will be restored to serving at the Pharaoh’s court. Joseph knows that this will happen, that’s why he asks the cupbearer:

But think of me when all is well with you again, and do me the kindness of mentioning me to Pharaoh, so as to free me from this place. (Gen 40:14)

In this week’s Torah portion we read that Joseph had to wait for two years to get out of jail:

After two years’ time, Pharaoh dreamed that he was standing by the Nile, when out of the Nile there came up seven cows, handsome and sturdy, and they grazed in the reed grass. (Gen 41:1-2)

Why is the Torah even mentioning this? Why did 2 years have to pass before the Pharaoh had a dream that only Joseph could explain?

According to Midrash Bereshit Rabbah Joseph had to spend two additional years in prison because the Divine plan for the world and the people of Israel had to be fulfilled. But the Midrash adds one detail: these two years correspond to the two words that Joseph “inadvertently” said to the cupbearer:

But think of me… and [mention me] to Pharaoh… (Gen 40:14)

Joseph was punished because these words show his desperation, and at the same time his lack of faith in the Eternal. Joseph sinned because he did not have trust in the Eternal, but instead he was relying on one, ordinary person (which actually sounds quite rational, considering the possibilities and limitations and the strengths and weaknesses of an average person). Joseph was punished because he was a tzadik, and Adonai medakdek im tzadikim k’chut ha’saara – Adonai is scrupulous with tzaddikim even to a single hair.

The essence of being a tzadik is therefore extraordinary scrupulousness and completely entrusting God with one’s life, in every aspect of one’s life. Everything comes down to fulfilling God’s law and to faith in the Eternal; since everything that happens in our lives comes from Him (including of course various punishments and rewards). But on the other hand in the rabbinical tradition we have a clear doctrine stating that we should never, especially in difficult situations, expect that a “miracle will happen” and we shouldn’t rely on such faith:

A person should never stand in a place of danger saying that they on High will perform a miracle for him, lest in the end they do not perform a miracle for him. And, moreover, even if they do perform a miracle for him, they will deduct it from his merits. (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 32a)

So is there a contradiction between these two concepts? No, if we define more precisely what faith in God is. First of all, faith in the Eternal does not come down to believing in miracles. The great majority of paths that God shows us in our lives do not have a miraculous or supernatural character, but are rather completely ordinary and natural. Relying on miracles is perceived as “testing God” and is forbidden:

Do not try the LORD your God, as you did at Massah. (Deuteronomy 6:16)

Actually in Massah the Israelites did try God: while standing in front of the Horab Mountain, waiting for Moses to miraculously retrieve water from the rock for them, they asked:

“Is the Eternal present among us or not?” (Ex 17:8)

Let’s go back to the questions we asked at the beginning: How should we live? On what basis should we make life choices? Should we trust God, ourselves, or maybe other people, for example those from the government? Or maybe we should trust only some people, or for example experts and science and technology? Certainly we shouldn’t put all our eggs in one basket and not leave everything to God, whom we should nonetheless trust. So in each situation we should have a multi-prong approach and have several alternative plans. We should trust both people and ourselves, as well as science and technology, but consider each of them with prudence and necessary critical thinking.

Trusting God entails mainly fulfilling His commandments and to bring real values down to earth. And when it comes to our expectations towards Him, then yes, we can expect from God help in every life situation. But we shouldn’t expect that God’s answer will have a miraculous, supernatural character or that it will be exactly as we wish. God usually offers us many different solutions; they are not always what we’d imagined they would be, although they often come close. Joseph trusted one possibility; a possibility that God didn’t actually consider in His plans.

God’s answer can come in different shapes: for example the Eternal gives us wisdom as well as inspiration and motivation to act and He removes the obstacles standing in our way. But in order to access His help and protection, we must open our hearts and minds to the world as widely as possible, so that we can notice everything that the Eternal has planned for us, since everything that happens around us is an element of the Divine plan – usually an element “which is not aware of itself”.

Shabbat Shalom!

Translated from Polish by: Marzena Szymańska-Błotnicka

This d’var Torah was commissioned by Beit Polska

– Union of Progressive Jewish Communities in Poland.